Entropy, 2023

Selection of Entropy on view at I Feel Everything At a Moment’s Notice. Ed. Valerie, Lower Manhattan, NY

On Entropy

Text by Shawn C. Simmons

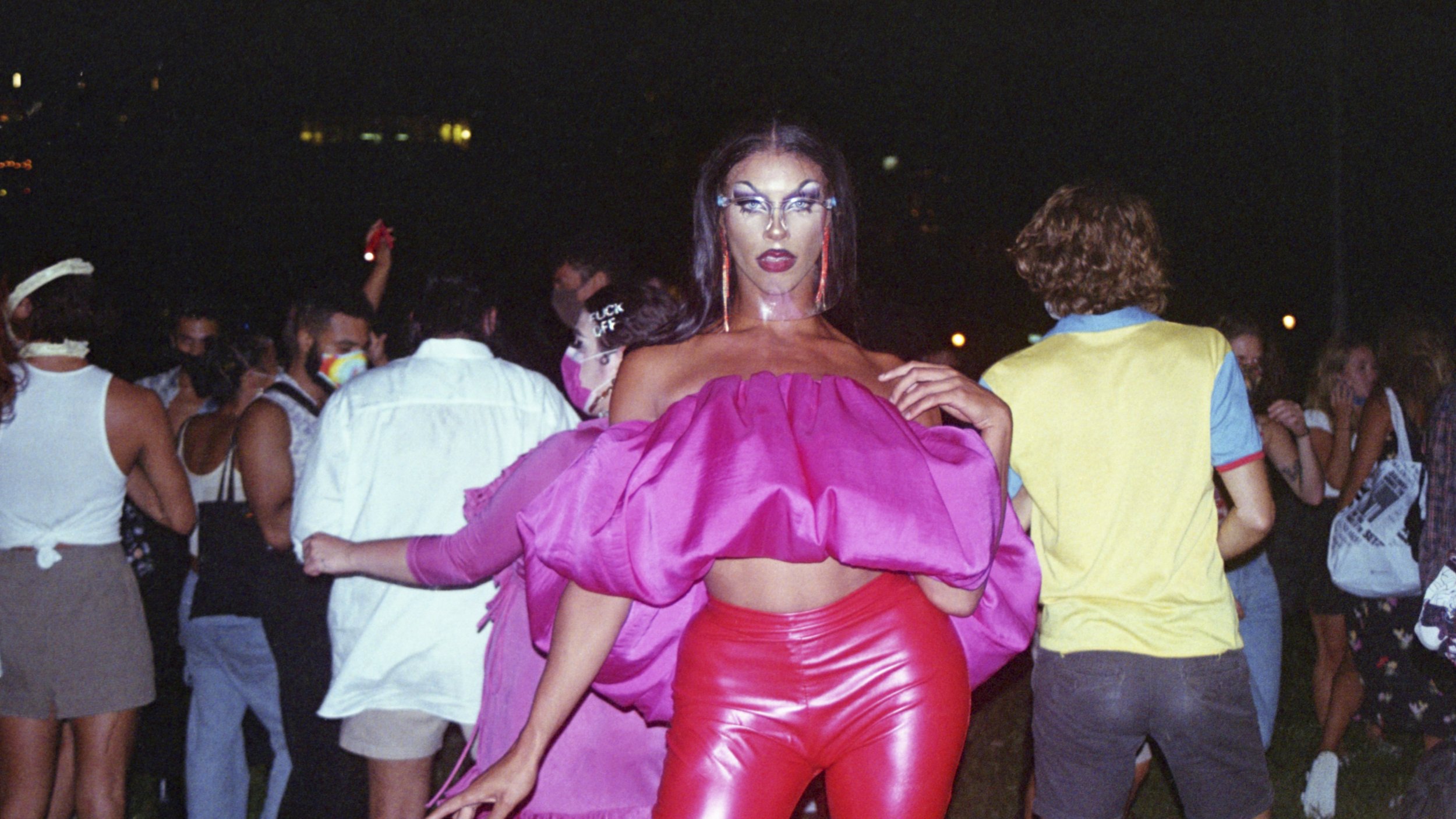

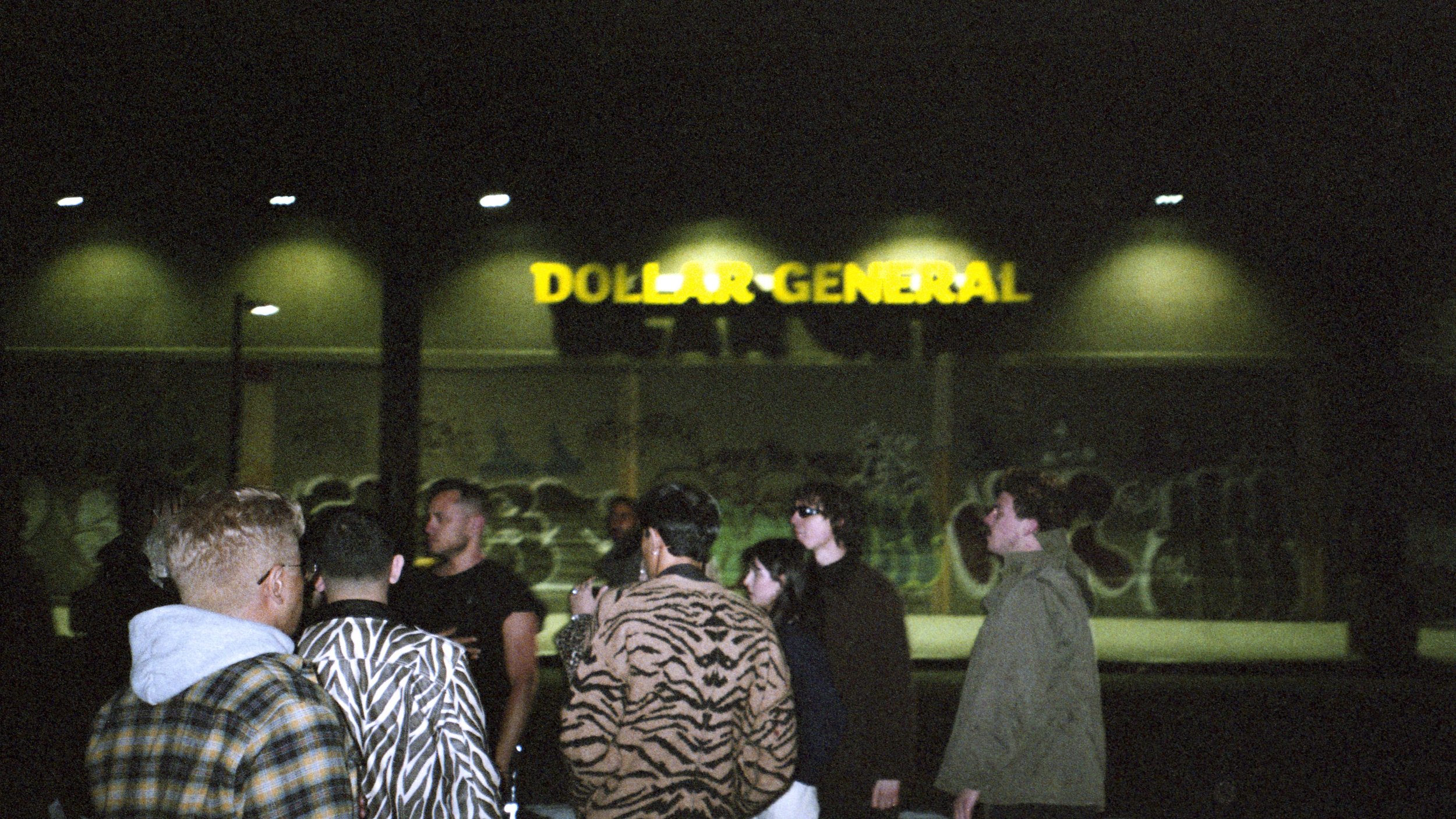

As I sift through the set of images Matías Alvial recently sent me, Entropy, I feel that I’m in constant motion, whisked away into scenes of chaos—defiant drag queens meet my gaze; spirited protesters pull me into the action; the occasional lonely landscape allows for a brief respite before I’m thrown into the next scene. From Santiago, to Brooklyn, to London—and with a few pit-stops along the way—Alvial documents the signs of the times, perhaps best (and bleakly) characterized in his photograph of roses pulverized into a concrete sidewalk: long forgotten, traipsed over, but retaining that optimistic glimmer of beauty. Here, destruction, survival, and liberation in the ever-evolving dynamic of human-versus-nature abound.

“I think I’m curious about far too many things,” he tells me over the phone. “I’d like to be everywhere all at once. Is that queer of me?”

Calling me on a late-night commute home from his studio, he walks past the AIDS memorial in Greenwich Village, just around the corner from the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual & Transgender Community Center (lovingly called ‘the Center’), two spaces with close ties to our long friendship. Just recently, he enacted a sort of guerrilla activist art project wherein he removed Felix González-Torres’s Untitled (Welcome Back Heroes) in its entirety from Galerie LeLong & Co in Chelsea. He stuffed his bags with the hundreds of individually wrapped Bazooka bubble gum pieces from the installation and made a symbolic procession to the Center. There, he installed the work in the bathroom, home to Keith Haring’s little-known gem of an X-rated mural, Once Upon a Time, from 1990. These values—of removing iconic queer work from the white cube, of making the private public—guide his personal philosophy and artistic practice.

When he mentions this, I’m transported back to the queer activist group meetings we attended at the Center. While I was introverted and took a more logistical approach to the group’s work, Matías was at the center of the action, placing his body on the front line of protests, often armed with a camera to document the good, the bad, and the ugly that come with struggles for liberation.

That fighting spirit has remained a through-line in his practice, but this series marks an entry into territory that is notably less pugilistic. His interest in the specific human textures of liberation lends itself to images that feel warm, humorous, and a little rough around the edges. The Chilean-born artist, who has been based in New York for the better part of a decade, has built a dynamic multimedia practice that reflects our changing times. “It’s actually quite funny,” he says, “because I see a lot of the rivalry that exists between mediums like painting and photography. I think being in the middle of that dialogue often puts me in an awkward spot. But it’s fun to criticize both mediums as I try to justify my own practice.”

He credits the diverse practice of Lyle Ashton Harris, for whom he worked as a studio assistant, as the main inspiration for beginning a formal practice back in 2019. “Working under [Harris] gave me so much insight on the theory behind photography: He used to tell me that ‘once you start reading, that’s when things really open up.’” Harris, who is a tenured professor at a top art school and former Guggenheim Fellow with an internationally renowned practice, regularly asked Alvial to scan the readings he assigned to various studio and theory classes, which ranged from Sontag’s theories of photographic agency to the candid notebooks of street artists: a bargain education. “Since I didn’t have any formal arts education of my own, it seemed like a good opportunity to learn about art and theory without paying thousands of dollars to read about art and theory.”

Above all, Harris urged him to start documenting anything and everything—his daily life and rituals, interactions with friends, family, and strangers—through photography and journaling. The candid remains at the core of Alvial’s photographic practice: at a time in which so much art photography is about “making pictures,” it signals a refreshing return to realness. Sontag touches on this lack of formality as the key notion which differentiates photography from other media. She argues that photography is a form of violation of the subject: “By seeing them as they never see themselves, by having knowledge of them that they can never have; it turns people into objects that can be symbolically possessed. Just as a camera is a sublimation of the gun, to photograph someone is a subliminal murder—a soft murder, appropriate to a sad, frightened time.” We might also understand this as the fundamental ethical hazard of photography.

In this light, Alvial’s work has drawn comparisons with the early work of another mentor. Ryan McGinley, who began photographing as a scrappy downtown kid in 1998, has become synonymous with candid portraits of people in moments of intimacy and unmitigated joy. McGinley and Alvial share these themes in their work, with several photographs acting as diaristic reports of friends smoking joints, reclining nude on the beach, dancing in the rain, and enjoying their dollar pizza slices post-debauchery—a tradition of raw downtown photography established by figures like Nan Goldin and Larry Clark in the 1980s, a vastly different cultural moment in terms of queer perception and acceptance.

The social aspect of a photographic practice has been a new challenge to navigate, and a marked departure from the early days of Goldin, Clark, and McGinley, when one could live in a Soho cold water studio for fifty dollars per month. Today’s New York photography circuit is small, moneyed and insular, largely built around exclusive parties, fashion line launches, and PR campaigns. It’s a difficult game of dancing around the glamour and narcissism that seem to be somewhat unique to the medium of photography. “Everyone wants a photographer on hand, but they’re not necessarily interested in the deeper aspects of the practice,” Alvial tells me. “When my practice was more focused on painting, I would have my little show openings, and that was that. When you throw the title ‘documentary photographer’ out there, a lot more people are suddenly interested in having a follow-up conversation.”

This selection of images in Entropy is a bold attempt at parting ways with the emergence of elitism in photography. The work distinguishes itself through an unabashed inclusiveness—a party in the best way. At the heart of Alvial’s practice is the exploration of identity and connection, and more recently, an interest in documenting queer experience as a tool for imagining better futures. If we consider entropy to be a gradual decline into complete disorder, these images would seem to find comfort in that disorder. These miniature snippets of reality allow us to find solace in the chaos of it all. Milk gets spilled. Roses get discarded and crushed. Many people will probably not dump their racist boyfriend. However, figures like Serena Tea and Chiquitita, in their confrontation with the camera lens, welcome us into the turmoil. Amid scenes of protest, of celebration, and of solitude, they reassure us of the possibility that everything is going to be all right.

This image set ends, appropriately, with a nod to the serenity of Boy Beach. A new take on the tradition of landscape painting, several nude boys emerge from the grassy dunes in a Larry Mitchell-esque scene of utopian fantasy. Here, human versus nature reaches a critical juncture: they exist, at least for now, in harmony with one another.

May we all find our Boy Beach; may we all embrace the chaos; may we all be all right. Whatever that means.